Erin Harrington reviews the Court Theatre Youth Company’s production of Boys, 12 May 2021.

The Court Theatre Youth Company’s excellent production of Eleanor Bishop’s Boys is a raw and angry show that asks questions about gender, power and tradition. Bishop’s script deconstructs Greg McGee’s landmark play Foreskin’s Lament, a scorching account of the fractious place of men and masculinity in a changing society, first produced in 1980 just as conflict about politics and sport was exploding. This play takes the original’s interrogation of rugby culture and national identity and turns it back on itself, creating an urgent and forceful work that demands meaningful change. The young company, nineteen actors aged between 17 and 21, are uniformly strong. They deliver a provocative, devastating 80 minutes with both clarity and conviction.

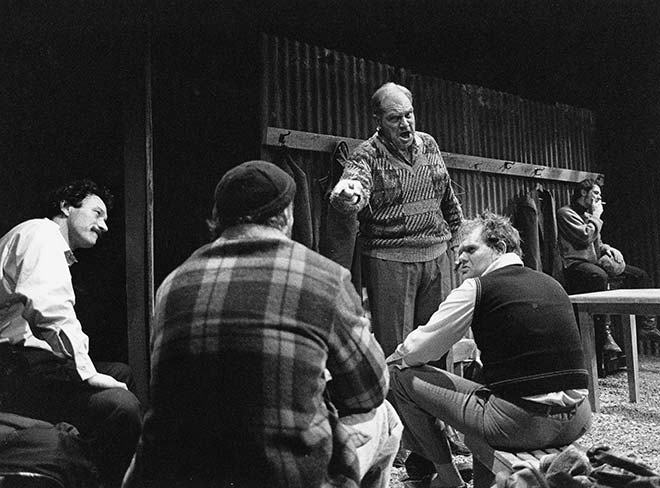

A large part of McGee’s first act is played straight. As we arrive, the ‘ya ya ya ya ya’ of Th’ Dudes’ drinking anthem “Bliss” plays over and over again, hypnotic. We’re in the locker room after a rugby game with the senior members of the team. As they change, make homophobic and misogynistic jokes, curse, and fight, they are berated and encouraged by their couch Tupper, who stands in for a sort of mythic bygone golden age of rugby culture. Foreskin, the protagonist, lives in a state of tension between two worlds: the effete, forward-thinking liberalism of ‘uni-varsity’ and the more ‘authentic’, grounded, provincial life. It’s already a problematic distinction.

Captain Ken is concussed, because vice-captain Clean keeps kicking him in the head when the ref isn’t looking. So much for teamwork and fair play. In the second act of McGee’s play, which is set at a drunken post-match party, Ken dies in hospital after another Clean kick. The play thus interrogates the country’s values, which are steeped within masculinity and homosociality; as Tupper says, ‘the town is the team’. Rugby is posited as an escape from nagging wives and screaming kids and mortgages, but rugby is New Zealand – so who is included, and excluded from this vision of the nation?

Soon, the original play begins to break down, and this postmodern fragmentation opens space for some excruciating questions. McGee’s play is sliced into real-life discussions as the players also come to speak for themselves, commenting on the play text, repeating key phrases, and placing men’s dialogue in the mouths of women to ironic effect. They particularly critique the presentation of Foreskin’s (girl)friend Moira, the only substantial female part in the play, and her vacillation between witty ball-buster and facilitator of a male character’s personal journey.

The most significant rupture is when the ‘femenist panel’ [sic], who have been watching and whispering from each end of the stage, storm the pitch (so to speak) and claim the space from the seven young men who open the show. Led by lawyer Moira they outline recent high profile ‘incidents’ of sportsmen harassing, abusing, degrading or injuring women, re-enacting commentary in the media and citing depositions. It’s angry and sad, awful in its repetitiveness. The cast sit, in chairs scattered across the space, sharing experiences while cut off from one another. The case is clear, but always contested.

The rejoinder, of course, is always that boys will be boys, that our lads are good guys blowing off steam, that women asked for it or complained too much or just didn’t get it, that a wee slip up isn’t such a big deal, that a woman’s broken back is just a bump in the road to a sports broadcaster’s self-actualisation.

It’s banter, isn’t it?

Grounding this in the everyday forces reflection on how structures both perpetuate or protect such attitudes. It’s painfully relevant. Recollections of recent ‘issues’ at Wellington College compel us to think about how earlier this year young women from Christchurch Girls’ High School attempted to protest outside Christchurch Boys’ High School against damaging behaviour, non-consensual sharing of pictures, and crass online exchanges (notably, ‘feminism is cancer’). I see this morning that a radio station has been called out for a job ad promising BYO sexual harrassment Sundays and a workplace where you can still be free to make jokes; ha ha, indeed.

What’s changed in 40 years, in theatre, in society? Boys says lots, and not much. I crack up at a comment that the real impact of feminism is that a farmhand can wear a man bun. The company marry their own lived experiences with the provocations of the play: the stories young women and gay men share of harassment or sexual manipulation; the straight men’s engagement in normalised acts of harassment or sexual entitlement. They all acknowledge pain, confusion, and in the case of many of the straight men, complicity – knowing or otherwise – in the sludge of what is frequently described as ‘toxic masculinity’. These are conversations that are rarely had in constructive ways in public; the utility of theatre as a space for discussion is clear.

Beyond their strong charactersation, the cast have to be commended for their openness and bravery, especially as they come to eyeball the audience – a tricky thing to do. It’s clear that director Rose Kirkup and assistant director Vanessa Gray have led an emotionally challenging rehearsal process with strength and compassion.

In its final, emotionally fraught minutes Boys posits that there is a way through, particularly for those young men who’ve been born into a social structure that empowers them at the expense of women, whether or not the feel they have much individual power. The answer, the show suggests, is to open up, embrace vulnerability and empathy, reflect and do better, and build meaningful relationships.

The original play famously ends with Foreskin, ostensibly the good guy collapsing under the weight of fear and hypocrisy at the death of a particular dream of Kiwi masculinity, bellowing ‘whaddarya?’ in a powerhouse, fragmented monologue. It’s a phrase used to diminish, to cast aspersions on one’s masculinity. Bishop’s work, instead, marries this with a more open invitation as the cast chants ‘ko wai koe?’ – what defines you?

Overall, this is an energetic production with a clear artistic point of view. Traverse staging offers space for strong blocking and dynamic dance sequences, as well as some bold lighting, positioning the audience as if we are on the sidelines watching the game run up and down the pitch. The costumes, designed by Nephtalim Antoine, also position the cast into teams, albeit ones that blur gendered stereotypes. The boys, in their civvies, are in pinks and mauves and feminine silhouettes, and the femenist panel in more masculine cuts, marrying lace and femme makeup with business wear in strong reds, blacks and whites. Design elements express questions about how power is expressed and felt, and how it might shift.

The only real issue, a frustratingly common one in these youth productions, is that diction and clarity of speech can be dicey. In the studio space at the Court, an acoustically difficult space at the best of times, largely untrained voices can and do disappear. I’m glad to be familiar with the original play, but I wonder how some of the original text is interpreted by those who are fresh to it.

Nonetheless it’s an engrossing show. I’m glad the Youth Company has staged it, although I wish we didn’t need it.

Boys runs from 12 – 15 May 2021 in the Pub Charity Studio at the Court Theatre.

[…] few shows – this, Ladies Night, and Things I Know to be True, alongside the Youth Company’s Boys – have all been very strong, in spite of some considerable COVID-related delays and disruptions. […]

LikeLike