Erin Harrington reviews Every Brilliant Thing, written by Duncan Macmillan with Jonny Donahoe, directed by Hillary Moulder, at the Court Theatre, Friday 6 April 2024.

A content note to start: is it okay to call an interactive play about depression and suicide joyful? UK playwright Duncan Macmillan’s Every Brilliant Thing is a river of concentrated sunshine – a sweet-salty comic work, created in collaboration with each night’s audience, that argues for imagination as a powerful form of hope.

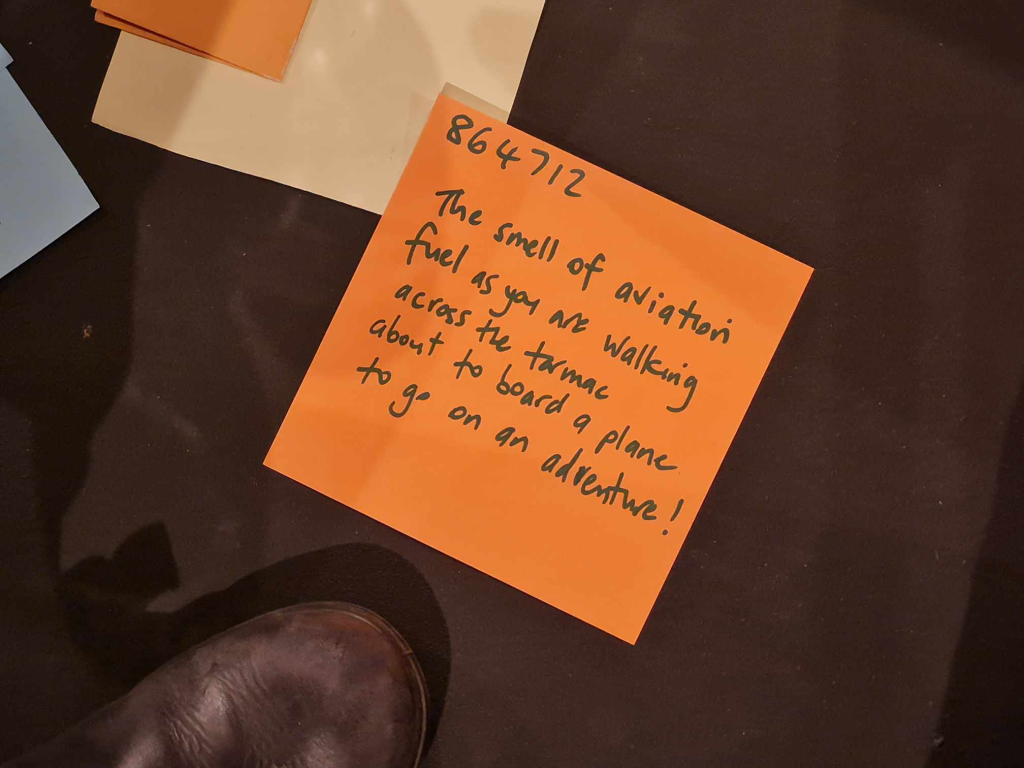

We’re seated in the round in the Pub Charity Studio, greeted as we enter by performer Trubie-Dylan Smith (who alternates throughout the season with Nick Purdie). Some of us are given tasks for later, all of us successfully softened up. It’s a slim production: a few black cubes on stage, some carefully placed props in the corners of the room. The house lights stay up – the work is a conversation. As we open, the show gets straight to the point. When our narrator was very young his mother tried to kill herself for the first time. His childlike (and perhaps emotionally astute) way of dealing with this was to write a list of every brilliant thing in the world – ice cream, staying up too late, roller coasters – and to share it with her.

We follow the narrator into adulthood as his relationship to the ever-growing list, his parents, and the world becomes more complex. We’re led through the joys of Power Rangers and Ray Charles, but also the impact of parental mental illness on children. We hear about suicide reporting guidelines, and the dangers of contagion. Macmillan’s empathetic script juxtaposes delight and awfulness, never going for the easy, pat answers. After all, is the list for mum, or for our narrator? Thankfully it is not a mawkish attempt to cheer up, Charlie, but a type of conversation between the family, and the world, that considers the detailed texture of every day experience. Can you ‘yes, and’ your way out of emotional crises? Yes, and no. The reality is that smelling fresh cut grass can’t counter the virulent persistence of chronic depression. Life can be absolutely shit, and brilliant things won’t solve that, but they might lessen pain by a matter of degrees.

Audience participation is a key element of the work, although I wouldn’t want those who fear interaction to avoid the show. The production trains us well, and quickly. At Smith’s behest we shout out some of the narrator’s brilliant things; he spins around, looking for the speaker, experiencing the list in surround sound. A handful of game people in the front row become important figures in the narrator’s life: his soul and jazz-loving dad, his primary school counsellor, more. Smith incorporates and directs these contributions skilfully, foregrounding play and not perfection. The carefully constructed sense of ‘this-ness’ in the room means that audience members embrace their roles with a remarkable sense of wholeness and spontaneity, fleshing out the world in sometimes unexpected ways. Within minutes of opening there’s that odd theatre magic, when the woman tasked with being a vet, there to put down the narrator’s beloved childhood pet Helen Bark in his first experience of death, is an actual vet who delivers the gentle pet-death speech with compassion. My friend and I and having a wee tangi and we’re only three minutes in.

This is a rare show in which the audience is all in – leaning forward into the conversation, vocalising, singing along with dad’s soul records, following instructions to participate in a way that I suspect exceeds everyone’s expectations. There’s that buzzy, intense feeling in the room as people laugh and cry, entirely focused on the centre of the room. By the end I wonder: is Smith the character, and the performer, supporting us through the show, or are we supporting him?

As the show progresses, I become really interested in the its tone, and the intersection of script and performer. Smith is a very experienced improvisor, and to those who don’t go to the theatre much, he may be familiar as one of the current hosts of long-running kids’ show What Now? I think this role as a children’s entertainer is very important here. His performance, and command of the room, is terrific. Smith carries the 80-minute show with a forceful yet vulnerable sense of verve and idealism, an extremely sunny disposition. It sits in careful balance with the gravity of the show’s content.

This chipper persona, and enthusiastically physical acting style, makes many of his frank descriptions of mental illness more approachable. They are frequently juxtaposed against charming storytelling and digression, in sharply punctuated reminders of oh, that’s why we’re here. There’s no agenda or attempt to manipulate – more a sense of incomprehension, and a need to understand. He’s not an unreliable narrator, but we must know that we are only seeing part of him, his cheerful denial self – the ‘inner child’ self who dealt so well (or maybe not) with trauma through optimism, as opposed to the adult self whose life and relationships are so much more complicated and greyscale.

This colourful production, directed intelligently by Hillary Moulder, and designed with care and economy by Tim Bain, Julian Southgate, Daniella Salazar, and Geoff Nunn, is a clear reminder of the power of art to impact people’s lives for the better. It’s an intense experience. At the end the room feels thick and prickly with emotion: elation, wonder, sadness, care. All suicide statistics are terrible, by New Zealand’s are especially bad, like a filthy stain sitting underneath a folksy ‘she’ll be right’ attitude; everyone in the room will have been impacted by mental illness and suicide in some way. But it’s not an trite exaggeration to say that theatre can also change lives. Storytelling can be a compassion machine that guides us, holds us, and lets us engage with the worst of the world in tricksy ways not permitted by other forms of discourse.

My experience of the show is thus framed by the news earlier in the week that the Suicide Prevention Office, within the Ministry of Health, is likely to be disestablished under the current government’s public service cuts, much to the surprise of the Minister of Mental Health – a reminder of the human face of enthusiastic ledger slashing. When I get home from the show, I see a news item from an hour prior suggesting sorry, sorry, maybe this will be walked back; some ‘learnings’ there, maybe.

Perhaps it’s stupid to be sitting in a show like this mulling over economics, but I also think about the precarity and paucity of arts funding nationally. Work, even lean shows like this, costs money. I’m thankful for the show’s sponsors, who have supported this work even though some (like Stuff) are facing their own crises.

Works like Every Brilliant Thing are important; I don’t think they are ‘nice to haves’. They are brilliant, in that they shine a light in the gloom, and remind us that collective joy and experience might be the enemy of despair.

Every Brilliant Thing runs until 4 May 2024.

[…] crisis that could undermine its ability to support work like this. I wrote the other day, about a very different but similarly joyful show, that the arts, which is often relegated to ‘entertainment’, offers an essential and very human […]

LikeLike